Joe Bradley — interview by Eric Troncy,

Frog 14, Fall•Winter 2014/2015.

Joe Bradley — interview by Eric Troncy,

Frog 14, Fall•Winter 2014/2015.

about painting but I discovered it there and it was like a feast, just looking at art through history. I’d known the usual suspects –Picasso, Georgia O’Keefe… The gods and goddesses…

— Did you like Georgia O’Keeffe when you were a student?

No, not really. Are you a fan?

— It took me a while to get interested but now, yes, I am.

There was an O’Keeffe exhibition at the Whitney a while ago and I spent a whole afternoon there and… Well, I just don’t get it… But yeah, in high school I was mostly drawing, these sort of one-liner gag comics. I didn’t really discover painting until I was 20 or 21.

— But then you knew it would be your medium?

It became obvious. I found I really enjoyed looking at other people’s paintings. That was the late nineties. I was in school between 1996 and 1999 I guess. Then I stuck around Providence –the town the school was in– for a year and a half and had a couple of aborted attempts to move to New York. Most of my friends had moved to the city, that was the place to go. I split for New York after a year and a half. I lived with my girlfriend at the time, and a couple of other friends in Bushwick, which now has become really chic –it’s the neighborhood that young creative people move to now– but at the time it was just a shithole. I lived there for maybe four years and I don’t think I walked anywhere but the corner store and the train station. So I have no real memory of Bushwick. We lived above a coffin factory.

— Well, that is extreme…

Yeah, they were making coffins for Hasidic Jews. There is a style of coffins the Hasidim go for; it’s like a simple pine box. We lived in a kind of loft, it smelled like cat pee. When you walked down the hall to the apartment there was a giant hole in the wall into the next place and there was a guy that lived there. He was a sweet old guy and he would be sitting on his couch in this really fucked up apartment, smoking crack and watching television at all hours. He would smile and wave when you walked by …

— Did moving to New York match your expectations?

Oh Yes! New York was a lot of fun. It’s a great school of, you know … Life and art. A great place to learn how to be a grown-up.

— Was it easy to be part of the art community?

The art world was kind of intimidating. I would go to openings sometimes but I would always leave very quickly. But in the end, it’s a pretty easygoing scene. You know, if you were an actor and you moved to Hollywood, and you wanted to meet Tom Cruise, that would probably not happen. But, you know, if you are a young artist and you really want to meet Mathew Barney, if you go to a lot of cocktail parties, chances are you would be in the same room as him and you could introduce yourself. It’s a small world.

— So CANADA was the first gallery to propose a solo show?

No. Before I moved to New York, I had a show with a gallery in Boston called Allston Skirt. Kenny Schachter saw the show in Boston and was interested. He called, I had no idea who he was, and I remember –it was back in the days of answering machines– coming home and listening to this message, and calling Dike Blair who was a friend asking if he knew who this person was. He said Kenny was a cool guy! So Kenny came over, and between the show in Boston and the time he came to the studio my work had really changed a lot. He liked the new stuff and proposed that we do a show, so I had a show with Kenny.

— What was the new stuff like?

The show he had seen in Boston was landscape paintings, which is what I’d focused on in school. Picture postcards landscapes like sunsets, tropical scenes …

— Do you know where it came from? Were you influenced by someone in particular?

I was looking at Marsden Hartley and Milton Avery, that kind of stuff. I had an earnest interest in landscape paintings in school, but I couldn’t bring myself to paint a straightforward landscape. I had to inject this bit of irony into it. So this is what Kenny saw in Boston. The new stuff he looked at … Well, the imagery was gone. They were small; ugly abstract paintings, and painting-like objects. Like plastic stapled over wooden stretchers.

— When you decided to move from landscape paintings to abstract paintings, did you think it was a definitive move?

When I was in school I started this kind of routine. I would work on what I thought was my “real work” during the year. And then, during the summer time I would do something else. It was like a little vacation. You can look at my work from the past 15 years and I’m still doing it, you know. So the abstract things had come out of that, the summer project … And they ended up just being more compelling and more interesting to me than the landscapes.

— What happened between that moment and the Whitney biennial where it all changed?

Well, the body of work I was making around the time of the Schachter show, I didn’t want them to function like normal paintings. I didn’t want the viewer to get caught up in the details, color, composition. I wanted the paintings to project some sort of personality, I suppose. I was hoping they would send off a signal, in the same way that a person does if you are in a room with another human being. So making these kind of figure-like shapes out of groups of monochromatic canvasses, I thought was a straightforward way of making that explicit, that desire to have them function in the same way as … This sounds insane when I say it out loud…

— Well no it does not! I remember hearing you talk about the way when a TV that was on in a bar for instance would draw your attention to it, even if you were not interested, it establishes a sort of unavoidable relationship between the viewer and the screen. So you were establishing a comparison between this and a quite similar situation of a painting in a room, and I totally relate to that.

Well, if you are in a bar and there is a baseball game on the TV, it’s almost impossible to keep your eyes off of it, even if you have no interest in baseball. Painting has the same kind of effect on me, it doesn’t matter what the painting is. There is something about the screen, and paintings are a sort of screen … they are like doorways. It’s like your ticket out of the room…

— Do you call them “Modular Paintings”?

Yeah. Although somebody pointed out to me recently that that would suggest you could move them around. They aren’t meant to be interactive in that way. Everybody calls them “Robots”, which I’m not so fond of. Those paintings were a real leap for me. It was the first time I made something that felt very much my own.

— During this journey, how did the paintings referring to abstract modernism appear?

They appeared rather slowly, out of drawing really. When I was making the Modular Paintings, I was drawing on the side, drawing all the time. So I think the desire was to create a sort of marriage, drawing and painting. I wanted to make drawings with the presence and scale of paintings. So this resulted in the Schmagoo paintings. It was a stab at painting again. Like pressing the reset button. So the paintings you’re talking about, the big abstract paintings, grew out of the Schmagoo paintings. In baby steps. First a little bit of color, and then a little more and a little more … Voilà!

— Yeah but… How does it work? Is there a moment when you know the painting is finished and great? Does it take a long time? Do you always reconsider? And by the way, are you painting on the floor?

Yes, for the most part, I paint on the floor. Then I’ll hang them up and look at them on the wall, like you would look at a painting. Then maybe I’ll work a little bit on the wall, and then back on the floor … But the question of when … I mean it’s difficult to know when they’re finished, and it seemed in the last couple of years to become more and more difficult to know. When they look alien, when they look unfamiliar …when I look at a painting of my own and I can’t really unpack it and retrace how it came to be, then it’s finished. If I look at it and it feels like looking at somebody else’s painting, basically … Then I can send it out into the world.

— When you look at them, it seems they’ve been taking a very long time to be the way they are.

Well that’s true. I mean relatively speaking. They probably take a year or something like that to make. But you know, I’ll work on something a little bit, and then it’ll kind of hang around and I’ll look at it …

— Are you working on many paintings at the same time?

Yeah. Typically it would be … I mean for better or worse there’s usually some sort of exhibition on the horizon. So I’ll think, “I would like to make 12 paintings for this show.” So I’ll start 12 paintings around the same time. I never worked on one painting at a time; it’s always a group. It’s like a horse race: one will lead the pack and the other ones have to catch up. They sort of bootstrap as a group.

—You paint them on both sides …

Yes. That began as a sort of fluke. I was painting on this particular canvas, this Turkish linen, that has a really nice feel. I discovered it while I was working in Berlin. It’s different from the kind of stuff that you could just go pick up at the art supplies store. I couldn’t find anything like it in New York, so it was a drag, you know … I had to be frugal with this stuff. So I was started working on both sides just to make the most it. I ended up enjoying the effect –well not only the effect, the effect was that the oil paint would bleed through the canvas and create a sort of ghost on the other side and I liked the look of that– but also the process. I paint on one side, and if I become frustrated with that side and I turn it over to work on the other side. Right away you have the bleed through to work with. Or you turn it over and find that the other side has picked up some interesting schmutz from the floor … Yes! There’s this real back and forth. At some point I looked around and I realized I had landed on this really weird way of painting. Working with the canvas laying flat on the floor … it’s closer to drawing: if I draw I don’t pin the paper to the wall, I draw on the flat surface of the table. You don’t really get to see the thing until you hang it up. You have this sort of surprise when you hang it on the wall. It’s a nice gimmick.

— Are you often satisfied with what you’ve been doing or are you always overly critical, wishing the canvas would have a third side so that you could turn it one more time?

Of course, I am very critical of my own work. I’m going to start taking it easy on myself though. I want to find a way to make painting easier and more pleasurable.

— Because it’s not?

It is very pleasurable, in a sense, but it is also super frustrating. There is a lot of tearing out hair.

— Well, about that, these paintings seem to please people a lot!

[laughing] Painting born of such suffering!

— I know! But it must be something special when something you’ve done make people happy! This is something I, as an art critic, wouldn’t know, of course…

It’s a little surprising that it’s been met with such a positive reaction. It makes me feel like I’m doing something wrong! (laughs)

— It is for this reason you’re changing styles very brutally sometimes?

No. Of course, I’m aware that there are people who are looking at the work and thinking about it and I have that in mind, but the changes are rather an effort to keep myself amused and interested, rather than to keep an audience amused and interested.

— Some paintings today, even great ones, seem to quote a lot, from Old Masters or more recent painters. Your paintings do not seem to quote anyone in particular, but it’s like they’ve always been around. They are familiar in a way. They seem to have a really natural place in painting history, we see where they come from, along this road that would be the road painting has taken since the beginning of the 20th century, and their position on this road seems very normal –despite their curious aspect. But your own manner makes them seem like a natural element along this road. They seem informed and free at the same time.

Well, you absorb Art History, and of course the idea is to sublimate that in the work and to come up with something that feels and looks like your own. So … that’s a nice thing to hear. There are times where people have said to me that it looks like Abstract Expressionism or it looks like Twombly, Basquiat, Schnabel … It’s kind of a lazy observation. If you were to hang one of my paintings next to one of Schnabel’s …the two really have very little in common.

— You’ve been doing sculptures as well, recently?

I’ve just been sort of dipping my toes in. It’s a nice antidote to painting.

— Did you need an antidote to painting?

I think now is one of these moments … I just haven’t painted in a little while. I like to take a break every now and then. Step back from the whole thing, the way a painter steps back from the painting. Just to take a look, to reevaluate …

— So you’re not working on any painting right now?

Well, I’ve been painting. I’ve been making Modular Paintings. Revisiting the older work. Those are paintings, for sure, but painting them is very different than painting these oil paintings. It’s really like, blue collar … It feels like you have a job all of a sudden. Just rolling on the paint …

— Well, yes, these ones look like there is an idea, some work to do, and you know when it’s done. It’s probably a very different process.

Well, the oil paintings arrive slowly, through improvisation. With the Modular Paintings I make series of formal decisions –scale, material, color– I give myself an assignment …

— The show we did together at Le Consortium brings several paintings together, did you ever have the chance before to see so many paintings from different periods and styles all together at the same time? How does it feel?

It was easy and fun! It’s like seeing some old friends. Most of these things, you spend a lot of time with them, you hang them up, and if you’re lucky they go out into the world and end up in somebody’s storage … So you don’t see them again. So it’s a treat to see them again. I haven’t really kept any of my paintings. I can’t live with my own work …

— There is not even a single painting of yours in your apartment?

Not until very recently. I gave my wife an old painting as a gift, so now there’s one hanging in our kitchen. But it drives me crazy. I can’t relax around it …

— So, you have three kids right? How old is the eldest?

He’s about to turn ten.

— Does he thinks it’s cool to have a dad who’s a painter, doing these funny images that probably do not relate to anything in a 10 year old kid culture?

You know … he’s grown up around it. He’s a great critic. Very blunt. He doesn’t mince words!

— He’d probably focus on the color to make up his judgment … They are so special, especially the newest ones, sometimes the palette reminds me of Pierre Bonnard …

Yes, that one has an unusual palette. If you walk through the show, some of the works are five or six years old and some are very recent. There is a palette that’s pretty consistent throughout. In the Modular Works as well, there is a sort of baseline and then deviations …

— The most recent ones seems to be more …

Pink? (laughs)

— Complex, intense even.

Yeah. Those paintings really went through the wringer …

— When we were working on the show we thought we’d borrow a painting that belongs now to Richard Prince. What does it feel to know that? Do you know him personally?

I met him a couple of times … It’s an honor to have an artist whose work you respect express interest, it is a big deal, it really means something. Richard Prince’s work I’m very fond of, so …

— One of your paintings was recently in an auction at Christies. How do you feel about that?

It’s weird. One of the great things about painting is that you have a lot of control. You don’t need any money to make a painting, you don’t need a gallery. You don’t need anyone’s approval. You don’t need to collaborate, you don’t need to wait for a green light. So the auction thing feels strange because it’s out of my hands. It adds a sort of subtext to the work that, to my mind, complicates things. All of a sudden you have the specter of money hanging around. Money is good gossip. Everyone loves money and it’s easier to talk about than painting. You know, it’s like having a kid and the kid grows up and gets involved in some sort of money laundering scheme and you’re just sort of helpless … You just watch. But in painting, you know… If your career goes down the shitter and no one cares anymore, you could still make a painting. It’s not like being Mel Gibson, thinking “Fuck! I’ll never work in this town again”! No one can say that to you. Painting is such a low-tech activity, you could burn every bridge in the art world and you could still go home and paint.

— Do you get bad reviews sometimes? What do people say?

I’ve gotten some bad reviews. My work has been called “coy”. Jerry Saltz called my work “boring”… I had a really good bad review from this guy, Chris Sharp in Frieze magazine, he wrote a real take down of the Schmagoo Paintings show … So yes, I’ve gotten some bad reviews. I kind of get off on them, to tell you the truth. I like bad reviews.

— You said you’ve been recently experimenting with sculpture: do you know what your next move will be? Do you know what you’ll be willing to experiment with?

I think the paintings will probably end up looking more like the drawings. That’s all I can say in a way. There is imagery in the oil paintings, but it’s always buried. I guess I’m asking myself, “Why bury it? Why not just come out with it?” I’ll go back to work this summer and give it a shot. I have a show blocked out for about a year from now, so that will be the goal. It’s nice to have these things that demarcate. I’ve got nine months to come up with something …

— It does not have to be like that: some artists think about showing their work once it’s done, other ones need a deadline to put an end to what they are doing.

For me, a deadline is helpful. It gives a certain urgency to what is going on in the studio. You know that whatever it is you are working on will leave and live on its own. Last year I started a group of paintings and I thought, “These paintings won’t go anywhere. They’ll be in my studio until they are finished.” I just kept working on them. I worked half of them to death. In the end I found it difficult, because … Why stop? Who knows what will happen next?

— Do you consider it a job?

No. It’s not a job. Whenever it begins to resemble a job, I have to back off a bit. I don’t want to run a small business. I don’t want to provide someone’s healthcare. I want to be able to go in whenever I want to. I want to be able to go to studio and just sit there and stare for hours at a time … So if it’s a job, it’s a really peculiar job.

————

ow did it all start? When did you decide to become an artist?

Art was the only thing I was any good at when I was a kid. Drawing. I drew a lot in high school. When I went to University, I had no idea what I was gonna do. I hadn’t been introduced to contemporary art, I really didn’t know that much

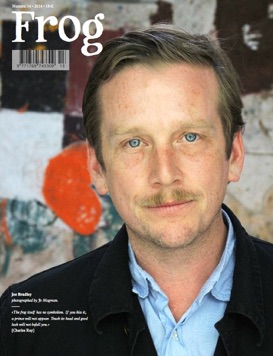

joe bradley

photographed for Frog

by jo malgrean.

Views from JOE BRADLEY

exhibition at le consortium, dijon. Photos andré morin.