Fredrik Vaerslev — interview by Eric Troncy,

Frog 14, Fall•Winter 2014/2015.

Fredrik Vaerslev — interview by Eric Troncy,

Frog 14, Fall•Winter 2014/2015.

— Would you like to be surrounded by artworks in your daily life?

Yes. I am not a collector of course but I’ve traded quite a few works with artist friends. Also at the beginning, when I started to sell my own artworks and earn money, I’d use that money to buy artworks by other artists. So I have a few. And the answer is yes; I love to be surrounded with artworks.

— Unlike other “young” artists, you did not sell your work immediately after school. How was school by the way, and who were your teachers?

No! I did not sell my work so quickly. I was enrolled with Matthew Buckingham in Malmö, and Simon Starling in Frankfurt. But if you study in Frankfurt you’re surrounded by a certain group of professors. I was with Willem de Rooij and Michael Krebber and Simon Starling, changing professors constantly. I also had Luc Tuymans, and some rather good meetings with Wolfgang Tillmans. I had a few crucial studio visits with Willem de Rooij, but this was about believing in a certain way of working. I was doing the Shelves Paintings, some collaborative works, and there was one studio visit in particular, two weeks before I left school, where Willem encouraged me to do a kind of thing I did not see clearly yet at that point. It’s hard to tell, but in my opinion, if I did not have that studio visit with him, I think I might haven taken a break. Also the influence of Michael Krebber has been very important to me. When I came to Frankfurt I had no idea who he was. There was a sort of cultish crowd around Krebber, a lot of people loved him, but at the time I was mostly interested in Michael Asher, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Dan Graham. As I said, I had been studying with Matthew Buckingham, so I wouldn’t say it was a “conceptual” starting point but there was definitely a “post-Whitney” crowd around him. The keywords for my education in Malmö were post-colonialism, feminism and social, geographical, political art. In Malmö –and I had a really great time there– I applied to the program as a painter and the day I started at that school I stopped making paintings. It’s a normal thing to do. As a former graffiti artist, I was interested in a certain relationship between painting and architecture, or environment. But then if you start reading a book like “Giving an Account of Oneself” by Judith Butler, which I read three times and still only understand one-tenth of; and go to the studio and try to paint at the same time, it’s hard to legitimize making a painting in any way.

— You mentioned earlier a studio visit with Willem de Rooij that was crucial to you, that would encourage you not to quit making art. In what way?

I don’t remember which year it was, probably in 2008. As I said I had applied to that Academy with a painting project, nine paintings in relation with some bus shelters. It was about traveling from my apartment to my mother’s house. You could say these were hyper-realistic paintings. Then for three years and a half I did not paint, not a single drop of paint, even though it was the only thing I wanted to do. The studio visit with Willem de Rooij was at the end, a week before the final exhibition, I had started to do a project based on a few of my mother’s sketches for what would be an ideal painting for her living room – I’m very influenced by my mother…

— Wait, is your mother an artist as well?

No, she is a nurse. But she is a very special person. She is very original; she has very precise ideas about colors, metal… If you lay out ten golden rings, with different shades of gold, she would pick up one straightaway and declare it’s the best one. It’s independent of any value; it could even not be real gold. This has influenced me a lot. Her practical solutions to things, ideas about renovation, things that we have in our house… It’s a homey, rural, pragmatic, practical way of doing things. She grew up with Gypsies, not Gypsies from Romania, Tatere Gypsies, from the North and West of Russia. They also have these practical things about magic, when a thing is beautiful. So I’ve been influenced by these things, but I was also studying with Simon Starling –which by the way was a great class– and if you want to make a painting that has a flower vase on a shelf, and your mother made a decision about the flowers, there is, let’s say, a sort of conflict there. So I felt embarrassed doing this new project, even if it was newer for me than everything I had been doing for many years, dealing with architecture and some political texts. It was a bit phony; the way things are fake in art schools when you’re confused and you’re trying to find your way and whoever your professor is influences you. So during this studio visit with Willem, instead of starting to discuss the work, the first thing he said was he didn’t like the flower arrangement, in the vase, and he started to rearrange the flowers.

— He would be concerned; he’s been doing this piece with a bouquet of a hundred flowers…

Yes! So suddenly, out of the blue he was redecorating my painting. As religious as it might sound, it opened up everything for me. I realized it was interesting to have someone else involved in helping to deal with a piece.

— So did you always know your way of dealing with painting would always involve architecture and decoration?

It wouldn’t always involve architecture and decoration, but if I think about all the works I’ve done and the ones I am doing now, you could always trace it back to architecture. Architecture not in terms of a Mies van der Rohe building, but architecture more like at my mother’s house, things such as the carpet, the couch, or the garage floor, things I’ve been living with. For the show I’m working on for the Andrew Kreps Gallery, works are made with a painting machine normally used to paint parking lots. It’s not from my mother’s house of course but it’s something I’ve been thinking about since 1986. After so many years, and now that I am an artist, that machine still intrigues me. If you have ADHD, if you are hyperactive – which I’m not – the idea of playing with that trolley is really fun!

— Oh! So ADHD is a disease you’re actually not suffering from. Sorry, you mentioned last time we met how hypochondriac you were.

Did I? Yes, I was part of this hypochondriac program in Norway. I was even filmed by my doctor for five years. Extreme cases get documented, for research and filing. For a long period, it was worse than insane, it was ruining my own economy. While I was a student in Frankfurt, I did not even dare touching my own skin in the shower. If I felt something under my armpit for instance, even the tiniest thing, I would immediately call the doctor and even with only two hundred bucks left on my bank account I would buy a plane ticket, hitchhike to the airport to go see my doctor

— Let’s go back to chronology. We were discussing this studio visit with Willem. That was at the end of school, right?

Before school, I was making graffiti for many years. That was my main occupation and I still think that some graffiti is very important and more avant-garde than most of the art I see. There was a really good scene in France in the early nineties, and the Norwegian scene, between 1981 and 1987, was as interesting as the Cologne art scene of the eighties. There is a group of six or seven guys and two or three girls; all of them could have been Rosemarie Trockel at any time. There was an amazing creativity going on there. Now it is not so interesting anymore, it hasn’t been for a long time. Anyway, if you’re making graffiti only for five or six years, it makes your life complicated. Even if, in my opinion, good graffiti and good art are very close. Graffiti is about attitude, and signature, and pace, more than execution. Think about Kippenberger, Polke, “bad painting”…

So I started this foundation course for graphic design that was very bad for me, and then a foundation course for painting that, in a way, was even worst. There were many things I wanted to do in life, like working in the fashion industry, or becoming a nurse. I was introduced to a few artists through the Foundation course who made me want to try to become an artist and go to the Art Academy instead. This cycle ended with the Willem de Rooij episode, and I went back to Malmö to study to get my Master of Fine Arts (MFA) – to take on a student loan in Scandinavia you need an official MFA, to get half of it off. But Frankfurt totally changed me. I had left Malmö with an idea of what I wanted to do for my MFA show three years from then, and I came back with a new insight about the world, about how I could deal not only with painting but also with production. During that time I mainly talked to my mother. I kept getting ideas from her and I’ve done many collaborative works with her – the first Terrazzo paintings for instance, which I did before my MFA. I did this painting and my mother painted things to match the background with the foreground: trees, birds…We did collaborative works for a year and a half, and one of these works was picked up by Standard Oslo.

— You understand this is a very unique strategy, to involve your mother with your art.

She’s still very involved. She’s been working with me on this show in Malmö that will open next week. It’s a homage to our dog, which died in November.

— You wanted to be a professional football player, is that right?

That was my dream from five to fifteen. But I hit puberty at nineteen; at the age of fourteen I was still 135 cm tall and the other kids were 180 cm tall, so I had to quit…

— Can you tell me about the way you paint?

I do paint on the floor because there is less pressure. I can’t imagine more pressure than painting a painting. I take any opportunity to get that pressure away from me: using tape and spray paint, or a machine, or letting the paint drip; to avoid touching it, so it’s not like the “magic touch” of Picasso or Josh Smith…

I’m always seeking these ways to have something in the work that relieves from the pressure. One of the things that works for me is to paint on the floor. But I’ve made some glass paintings for a show last year, and these have been painted looking straight at them.

— There is a sort of “face-to-face” with the painting when it’s on the wall, whereas you would have a very dominant position when it’s on the floor.

Totally! Maybe it’s a bit ‘cowardly’ to paint on the floor but I think it’s just awesome. I could go and paint everyday. There is no pressure then, independently of how much the canvas costs or where it should go after. It’s less ‘art historical” somehow, for me, less of a dialogue, one-to-one with the myth of painting.

— Do you paint because you have a show coming up or because you have an idea?

I paint because I have an idea. But having shows helps, of course. And this is in fact a very difficult question to answer. I am not Josh Smith, even though he is a good friend of mine and I’m a huge Josh Smith fan, but I wouldn’t be able to do what he is doing. I wouldn’t be able to simply go to the studio everyday and make a bunch of works and really be invested in that way, so it’s more show-related. Some people think it’s problematic to do a lot of gallery shows but I love gallery shows. The history of the place, the architecture…

— Yes, some of your works seem to be very site-related, and of course the idea of a painting made for a specific place raises a few questions regarding its future displays. Do they keep the memory of the place they were conceived for?

I did it recently for a show in Lisbon, the pieces were made specifically for the space, and I’ve been using the name of the place –and I really was thinking of Josh Smith when I was making these works– their logo, and that orange color as well. I love it when there is a starting point for a painting. I don’t go to the studio and just paint stuff. It’s curiosity-driven. A couch with paint stains on it, from whatever, from renovating the house, or even bird shit, or rain, it allows me to make some gestures I would never make on a blank canvas. I would never, under any circumstances, even with a gun to my head, go to the studio, stretch a blank canvas and start to do something with a stick. Some things happen, from shoes on a marble floor, from a sundeck … certain things happen when you work inside an environment, even in nature, that do not happen in a clean studio space. And those things I enjoy.

— Is this why you sometimes leave the paintings outside in the rain, like Edvard Munch?

I’ve done it for a show with Gio Marconi. They were filled with mildew, a toxic, very poisonous kind of mildew –I feel sorry for whatever happens with these paintings, I would never have them in my own home. I’ve put them outside for a year. I’ve been confronted with Edvard Munch, of course, and what he called the “horse treatment” he would give some of his paintings when he was not totally satisfied with them. He would just leave them outside through the winter. Thinking Mother Nature gave them something. I find it funny and amusing, to imagine him doing this makes me laugh, and also I find it very logical. For me –and I’m sure for many others who deal with painting– at some point you just think “This is not a good painting” and so you either throw it away, or paint on the other side, but you can also just leave it outside. If you live on the Riviera, maybe the sun will do something to it, there are so many things you can do, and I think Munch pinpointed this very well. To do this, to leave a painting outside so to make it better, in 1901, was outrageous. In my opinion, Munch is the greatest artist of all time. As a Norwegian, I might be not objective…

— Has it also been a handicap, to live in Norway?

I have a few very good friends who are very helpful, like Mathias Faldbakken – who does not live here actually but we’re e-mailing a lot –and from time to time I meet with friends in New York who have the same concern as mine about painting. And for me it’s never been an option to move to New York or Berlin. I hate Berlin. Anyway, it’s more peaceful here.

— Even now? There is a lot of attention about your work…

But that particular attention can stop at any time, it’s a fact of the art business that it could literally stop next month. I don’t get that kind of attention where I live! I live one hour outside of Oslo. My influences are what I choose to look at on the Internet, and whom I choose to talk to. I don’t feel any pressure whatsoever; the only pressure I get is if what I do is not good enough for me.

— The art world obviously changed radically between when you decided to study art, fifteen years ago, and now. Was it very difficult for you to face that change?

Not really. This might sound a bit naïve, and this is a super relevant question, especially in my position, when you sell a shitload of paintings and you work with certain galleries. But my gallery in Oslo takes a lot of the pressure away from me. The works I have bought from other artists, or traded with other artists, I have a very possessive relation with them, and I do treat them like jewelry. But my own work, I don’t care so much about it, except at this point it’s good if it’s not sold to someone who’s going to sell it at Sotheby’s the day after. But this is today, and this might change again in a month from now. I didn’t care about this a year ago, but there have been a few incidents recently with my work. So it happened, maybe it will happen again, but it’s outside of my control. And I took a teaching position at the University in Oslo.

I rarely go to openings; I think it is a pretty offensive environment.

At the age of thirty-one, I moved back to my mother’s, I was so broke –It’s not possible to be that broke in the Western world– I had only 200 Euros left on my bank account, I owed the State 70,000 Euros for my student loan, I had no job and my only options were to get a full-time job at IKEA, or go to my mother’s and paint inside her garage. This also explains why I left some paintings outside. I moved there in May 2010, started all these works outside, in my mother’s garden. In May and June the weather is really great in Norway, but then it’s replaced by something like Antarctica. And in October, as stupid as it sounds, I did not expect snow and suddenly there was 20 cm of snow on the ground. I could not even find the paintings anymore, under this solid snow all over my mother’s garden. I did not have the energy to dig in that snow, and I had no space to let the paintings dry anyway. I thought the snow would melt in November, but that year, in 2010, the winter was particularly harsh. The snow did finally melt in April, I saw the paintings again, and they were twice as good as before. And to be honest, at that point I didn’t know about Edvard Munch’s “horse treatment”. This kind of things simply happens, where I live.

— What you accidentally borrowed from Munch is now clear. What do you think you borrowed from Michael Asher?

I stole from him works that I don’t even know if they really exist.

I had a professor in Malmö; an art historian called Alexander Alberro –he now teaches at Columbia– and my best talks there were with him. He came very rarely, he wrote books about conceptual artists. He told me about John Knight –who was really unknown at that time inside my own circle– and Michael Asher, and this idea that certain things you do change everything around you. One of the things Michael Asher is credited for is that he was commissioned to do a work in Los Angeles (I have the feeling I change this story every time but it’s such a long time ago now, so it might be a lie and Asher is not there anymore) and this work was made for a huge property. He basically took thirty percent off of this property and gave it to the neighbor, moving the fence seven meters away. If this is true, it’s the most radical work ever, in a good way.

— Last time I saw you; you mentioned a movie about Agnes Martin.

She made this movie a few years before she died. It’s the most beautiful art film I’ve seen. If you don’t like Agnes Martin’s work, of course this film might not be appropriate. But if you like it just a little bit, it’s unique. In this movie, she is painting, and a film crew is there. She is sitting on her balcony, during four months, waiting for inspiration to come. There is nothing about this that isn’t completely insane. She’s not reading or anything, she’s literally waiting, and then she paints the same stripes again and again. I find it to be a very optimistic attitude, even though she herself doesn’t seem optimistic at all. She’s tense, she’s struggling with inspiration, waiting. I do believe that at some point, it sort of unfolds, somehow, it could be when you are on an airplane, or at a stupid moment; and then you get it.

————

o you bought an Albert Oehlen painting?

I almost bought an Albert Oelhen painting from Max Hetzler at an Art Fair. But that would have been bad for my own private economy.

Fredric Vaerslev

photographed for Frog

by pierre even.

Untitled (Canopy Painting: Orange, Cream and Yellow), 2012.

Primer, spray paint and white spirit on canvas / wooden stretcher 200 x 125 x 3.4 cm / 78 3/4 x 49 1/4 x 1 1/3 in.

Fredrik Værslev, 2013.

Installation view, Drøbak Kunstforening, Drøbak.

Sunny Side Up, 2012.

Installation view, Indipendenza Studio

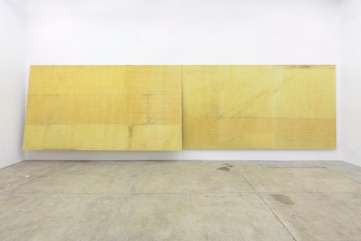

Groundhog Day, 2013.

Installation view, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York.